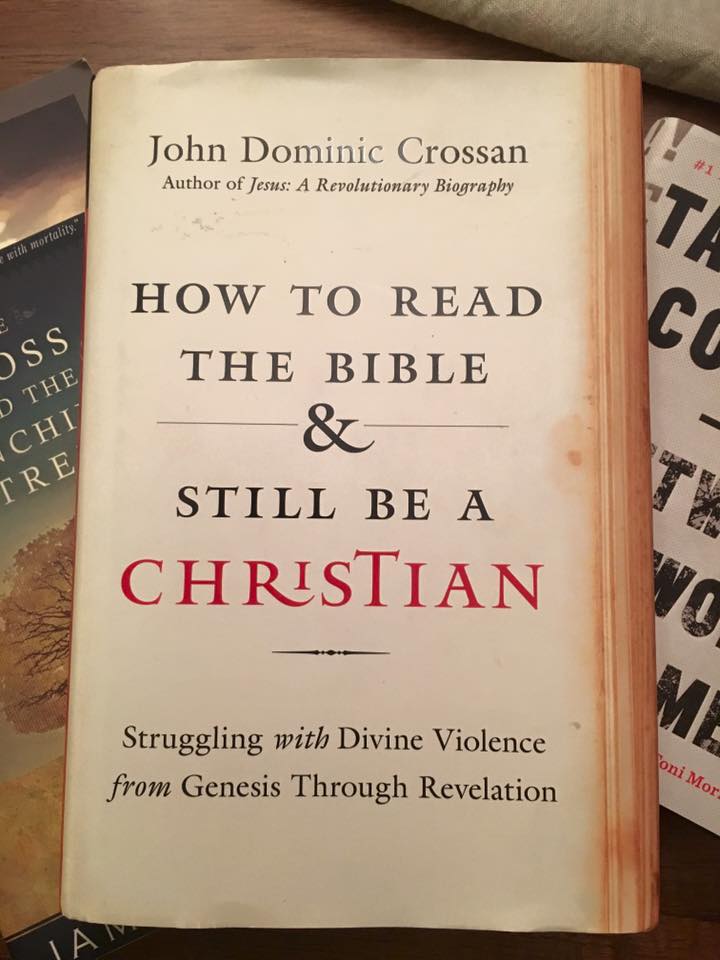

How to Read the Bible and Still be a Christian: Struggling with Divine Violence from Genesis Through Revelation

by John Dominic Crossan.

Crossan is one of the foremost scholars who has worked on the studies of the Historical Jesus. This latest book is a dialectical conversation between contradictory visions of God inherent in the Bible, those of a nonviolent loving God of justice and that of a violent God who brings justice through retribution. Born from his decades of biblical studies, archaeology and history (both ancient and modern), he presents a coherent hermeneutic for reading the Bible without losing your faith from the inherent contradictions.

He starts from the reminder that every text (Biblical and even Trump’s The Art of the Deal [my example]) is formulated and recorded in a specific context of history, time, sociology and political atmosphere. He calls that a matrix. Working through the principal sections of the Bible, from Genesis to Revelation, identifying the matrices from ancient Mesopotamia (in which Genesis emerged), the imperial powers of Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, Persia and finally Rome (the maternity ward for the New Testament), Crossan teases out the layers, or internal dialogue within the text between contradictory voices which seek first to affirm the radicality of God in the face of the powers of humanity and the corresponding normalizing response of civilization which works to to subvert and negate this vision of radical love and justice. Much of his ideas flow from the documentary hypothesis: the notion that the Pentateuch is a combined narrative redacted by four principal voices from the civilization of ancient Israel: these four sources came to be known as the Yahwist, J; the Elohist, E; the Deuteronomist, D, and the Priestly Writer, P. This is a highly complex theory, which I learned with most other Presbyterian clergy in seminary (or at least tried to comprehend to pass Old Testament). Crossan explains and simplifies a far from simple idea with multiple examples and illuminating clarity.

His overarching thesis and hermeunetical lens for reading the text of the Bible (did you know that word in ancient Greek means “library” – as it’s a collection of books and narratives…not just one unified tome?) is that “Love empower justice, and justice embodies love.” The Christian Bible contains a library of narratives that articulate the tension between the radical way that God calls us to know power (nonviolent – persuasion) and Justice (distributive – coming naturally from our response to what we have been given) and the normalcy of civilization which practices power as violent force and justice primarily as retribution to reinforce power.

I can’t do justice to the simplicity of his thesis. His writing, while probably horrifying to a literalist-reader of the Bible, is one that feels like an arm around your shoulder, inviting you to a safe discussion in which you can name the places in the Bible where you are stumped by what seems to be interior contradictions, such as when Jesus is the Prince of Peace, not resisting crucifixion and then at the Apocalypse seems to impale everyone with a flaming ninja sword before throwing them into a lake of fire. It might not be a book that everyone can read, yet it is a good one for Christians and non-Christian readers of the Bible to consider. It’s not just the Bible that is written in and from a specific matrix. Every text is. When we read the Bible as if it were written in 2005 we miss much of what it’s saying about human civilization over the course of history and how God, the God of the Bible, is calling us to a radically different way of living, loving and knowing justice. In itself it holds contradictions, later reactions of the judeo-christian tradition which sought to subvert and tone down the original vision of God’s radical love in the hopes of better fitting into society, to make less waves, and to gain more acceptance. In the end it’s a reminder that the God of the Bible is not one that seeks to institutionalize faith, distribute justice to those who deserve it, and love those who accept God – but rather a wildly different God who calls us to a new Way of being and seeks to turn our world upside down so that we might live right side up from love and justice.