Job 14:7-15; 19:23-27 & Romans 8:26-38

The past two weeks in our country have been punctuated with the conventions of our two major political parties. David Brooks, in the NY Times observed, “both featured one grieving parent after another. The fear of violent death is on everybody’s mind — from ISIS, cops, lone sociopaths. The essential contract of society — that if you behave responsibly things will work out — has been severed for many people.” [link to opinion piece: “The Democrats Win the Summer”]

The book of Job strives against a similar dehumanizing understanding: that if fear God, serve God, things will work out. And yet we see that’s not the case. It’s not that God doesn’t love us, but rather that the injustice of our world, evil in creation, the brokenness of our human condition are not simply erased. They too are part of creation. God created light from darkness, without destroying the darkness. The story of Job shakes the foundations of our faith. Why do we trust God? How do we envision God: as a bully who threatens us into discipleship submission? As an uncaring parent who justifies a lack of muscular love with hallmark hope? As one who walk with and alongside us in the dark and the light? Are we victims of creation? Are we participants in the unfolding vocation of it?

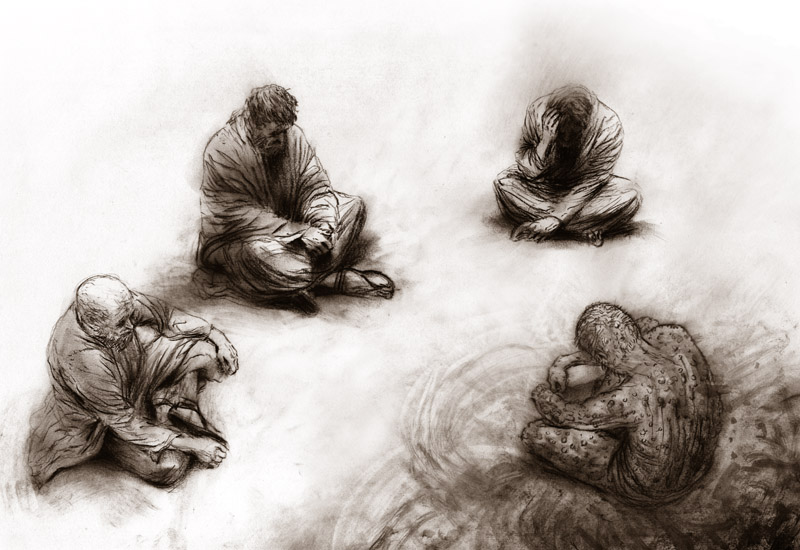

In the story of creation, what is before God speaks, is called in Tohu wa bohu (תֹ֙הוּ֙ וָבֹ֔הוּ) Hebrew, meaning “the earth was a formless void” (Gen 1:2) Throughout the Bible the word is used to also mean: futile, vain, confusion, meaningless, desolation. It’s related to wilderness (or desert) the place that resists God’s power into which the Israelites are driven by Pharaoh, where the prophets go to be tested, where Hagar goes to die in hopelessness; that which keeps us from God’s promised land. Job finds himself at see in the formless void of God-resisting chaos, sinking fast, without a life raft. He never imagined being there, doesn’t think he has acted so as to deserve it, disbelieves that God will deliver him from this despair God seems to have led him into.

We feel the same way at moments in life. How we see God shapes our reaction, our practice of faith (orthopraxis), how we in turn treat each other, as well as how we treat ourselves. But what about those born into radical poverty, existential brokenness in the two-thirds world from which there is no escape: a shantytown existence outside of Calcutta, sold by parents as a sex slave in Thailand, orphaned in infancy by AIDS in sub-Sahara Africa. What good is God for them? What good ordering of chaos does God bring to those we call the oppressed poor of the earth, the desolated powerless who live on less than a dollar a day, who will not find protection and help in their country’s government, their neighbor….

German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche wrote in his seminal work The Anti-Christ, against this working out for all, having seen that it isn’t doesn’t hold up in 20th century Europe.

What is good? – All that heightens the feeling of power, the will to power, power itself in man.

What is bad? – All that proceeds from weakness.

What is happiness? – The feeling that power increases – that a resistance is overcome.

Not contentment, but more power; not peace at all, but war; not virtue, but proficiency.

The weak and ill-constituted shall perish: first principle of our philanthropy. And one shall help them to do so.

What is more harmful than any vice? – Active sympathy for the ill- constituted and weak – Christianity…

He would advise Job, and anyone else not tough enough to stand up a fight, to lay down and die. His vision of order from the tohu wa bohu is one in which chaos must been beaten by the individuals who are hyper-strong. Unless you’re up for the task, and afraid of nothing, not even kryptonite, Nietzsche’s view reduces everyone to the ash-heap of deathly despair in the face of evil, suffering and chaos; when confronted with the reality of human existence.

In today’s reading of Job and his ongoing dialogue with his filled-with-advice friends he speaks of a glimmer of hope, like a seed, seemingly dead, which can find water and grow into a tree. While not hopeful for himself per say, he doesn’t negate the possibility and power of God in the world. In Romans Paul writes of this same radical hope that we see in the world not in strength and power but in weakness and worldly defeat (the cross of Christ). Far from being a hallmark-y statement encouraging us to pull ourselves up by our boot straps, they articulate the tension of light from the darkness, of hope when wandering in the wilderness, of faith over fear.

Questions for Active Reflection:

- When have you felt trapped in the wilderness, plagued by the thought that God is either targeting you or not protecting you? How have you experienced the wisdom of God as a mystery in life?

- How are you experiencing that today? Paul says not only that Christ is victorious, but that we are victorious through him. Yet the victory is different than we describe in human terms.

- How do you long for, need to see, or be reminded that we – you – are more than conquerors in Christ Jesus?