1 Samuel 1:9-11, 19-20; 2:1-10 & Luke 1:46-55

The books of Samuel tell the story of radical transformation that occurred in the life of Israel as that people moved from living together as a religious association of tribes to a centralized state with a monarch. Samuel is the main character, the prophet who finds and ordains the monarchs and exists as a prophetic counter-voice to their whims and fancies, pushing them to inclusive justice and God-centered authority. Curiously it’s the story of the people wanting a king, to be like all the other peoples of the near east; while God calls them to be different, unique, but acquiesces to their desires, giving them all of what comes with a king – good and bad.

Today’s selection tells of the origins of Samuel, born to Hannah the second of two wives, who although the favorite of her husband (Elkanah), is looked down upon by her sister-wife (Peninnah) and society, because she is barren: less than a full woman in the cultural perspective. The song or prayer of Hannah, her expression of gratitude to God for answering her prayer is a majestic poem, highlighting Hebrew thought and theology. It’s strongly echoed elsewhere in the Bible specifically by David in 2 Samuel 22; the poet in Psalm 113 and the Magnificat of Mary in Luke 1:46-55.

Luke, tells his gospel version of the life of Jesus for Greek-speaking people, who were primarily Gentile, or non-Jewish. Luke and Matthew are the only gospel to really tell the birth story of Jesus, highlighting different aspects. Curiously Luke is the only gospel to consistently focus on the group of women who traveled with and supported Jesus, presenting them as actors and participants in the gospel. And only Luke records this prayer song of Mary we read today.

The story of Hannah begins with her weeping in 1:7; and ends here with her singing a prayer of amazing theological development. It is her joy, but Yahweh’s power. The incredible change of Hannah’s status through this answer to prayer demonstrates the unique, transformative sovereignty of Yahweh who has no equal. Her prayer invokes the full spectrum of existence from war, food and children to life and death. Yahweh acts in a way as to birth justice, transforming the wrong into the right, lowering and raising in a way often foreign to our human notions of power, privilege and purpose. At the heart of Hebrew poetry (especially here) is Parallelism: a balanced repetition that repeats with a synonym, or contrasts (antithetical parallelism).

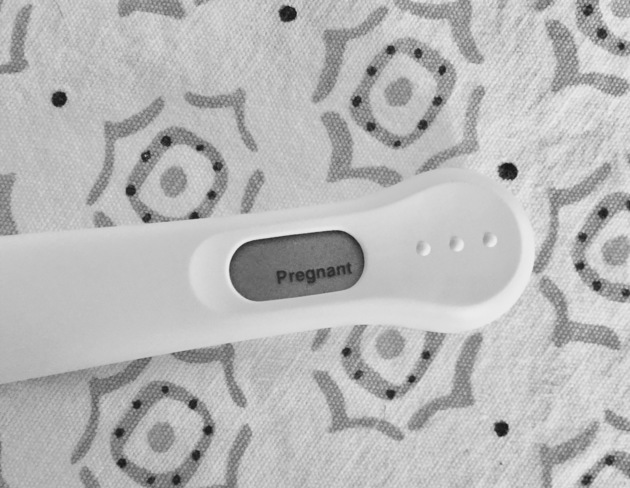

This prayer of Hannah’s is strikingly similar if not identical in theme, theology, the poetic use of parallelism, and in vocabulary with Psalm 113 and the song of Mary (known as the Magnificat) in Luke 1:46-55. They are poems pregnant with the possibility of God’s saving action and the divine purpose to turn the upside down world right-side up. They are “spoken” in anticipation of children to come, who will be a great judge and the messiah; yet they could be spoken by any mother (or father) at any time of any child-to-come. They point to the affirmation in our shared faith that our story is part of God’s unfolding story of creation, redemption, resurrection and justice in the universe.

Questions for Examen & Contemplation

- These prayer-poems are remarkably similar. Is it a question of plagiarism, a lack of originality, or a borrowing of the past language to say what is un-sayable? How are you shaped by the language of the Bible when you talk of and to God? Or about how God moves in the world? How is that helpful for you? How does it complicate our efforts to talk about faith with each other, and with those who are biblically illiterate?

- The story of Hannah is one of vindication. Yet within the larger story of Samuel it shows how Yahweh accomplishes many things through the divine will, working to reverse the ways of the world to bring about justice and righteous living. It’s not just spiritual or religious, but first social, economic and ethical. In what ways do you long for God to reverse the order of the world? How is your story part of this larger ongoing story of God’s radical transformation: making all things new?