1 Samuel 16:1-13 & Psalm 51:10-14

This week we hear another story of Call – that of David as the king of Israel. He is subversively crown (or anointed) by the priest Samuel (called to be a truth-teller in last week’s scripture of 1 Samuel 3). Here he is afraid of the current king, Saul. For Samuel is commanded by God to commit treason: to anoint a new king while the old one is still on the throne. He is afraid of the King, Saul. And he is divinely directed to Bethlehem: a city outside of the royal reach of Saul’s Northern Kingdom. Yet even there, the people are afraid too of the political implications of the prophet’s arrival (9:4). This story of a new beginning, of God’s sovereign power working within the happenings of human history, of the divine import not on the physical appearance but on something else, all of this begins in the tension of fear, anxiety and human trembling. This week we hear another story of Call – that of David as the king of Israel. He is subversively crown (or anointed) by the priest Samuel (called to be a truth-teller in last week’s scripture of 1 Samuel 3). Here he is afraid of the current king, Saul. For Samuel is commanded by God to commit treason: to anoint a new king while the old one is still on the throne. He is afraid of the King. (9:1) He is directed to Bethlehem, a city outside of the royal reach of Saul’s Northern Kingdom. Yet there the people are afraid too of the political implications of the prophet’s arrival (9:4). This story of a new beginning, of God’s sovereign power working within the happenings of human history, of the divine import not on the physical appearance but on something else, all of this begins in the tension of fear, anxiety and human trembling.

Saul is out as king for his disobedience and covenant breaking with God. Royal power flows first and foremost from a relationship with the Divine Maker, the Holy One in whose image we all are created. This is proclaimed by the prophet Samuel in 1 Samuel 13:13-14 and 15:26-28. Yet the new king, seems to be the farthest from what one would imagine – even the prophet Samuel. He thinks that the eldest son of Jesse will be the king, Eliab, who like Saul, is big, strong, handsome. Yet God sees beyond the physical, more than the visible. God chooses the youngest, smallest: the family runt – David (who still happens to be strikingly handsome!) The Apostle Paul talks of this paradox in saying, “God chose what is weak in the world to shame the strong; God chose what is low and despised in the world, things that are not, to reduce to nothing things that are, so that no one might boast in the presence of God.” 1 Corinthians 1:26-31.

Great philosophers and scientists have also remarked on the ways in which our vision is limited, and often fools us. German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, one of the fathers of post-modernism wrote “Sometimes people don’t want to hear the truth because they don’t want their illusions destroyed.” Francis Bacon, father of the modernist scientific method observed, “We prefer to believe what we prefer to be true.” John Stuart Mill, the father of Liberalism – our current belief in the primary importance of individual liberty – described our limited vision saying “He who knows only his own side of the case knows little of that.”

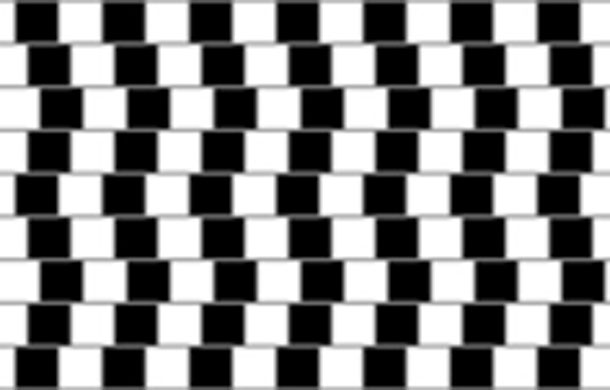

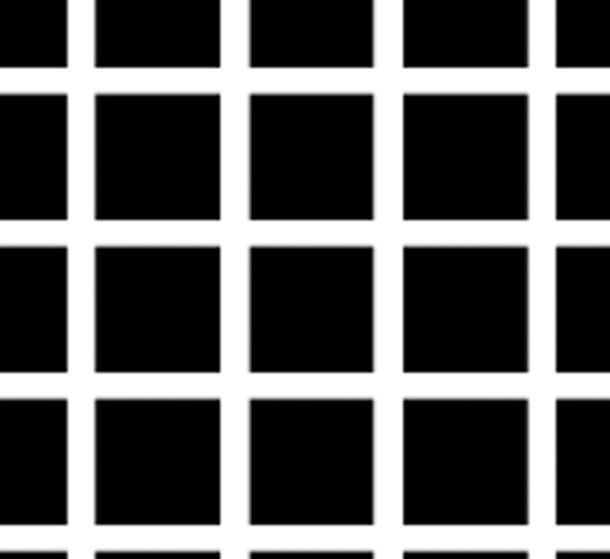

The pictures above are all visual illusions that demonstrate the paradox of what we see as not truly being there, or of seeing what we want to see. In the first image the lines running across the picture are actually parallel to each other despite what you think you see. In the second optical illusion, known as both the Titchener Circles and the Ebbinghaus Illusion, the orange circle on the left appears to be smaller than the one on the right although in reality they are the same size. (There is still a debate in psychological circles as to the exact mechanism and implication of this effect.) In “Rotating Squares”, the third image, at first this optical illusion picture may be hard to see, but if you begin to scan back and forth across the image you will notice that the squares in your periphery begin to rotate. As soon as your eyes stop moving, however, rotation will cease. And the fourth and final illusion, the “Hermann Grid”, named after Ludimar Hermann who discovered it in 1870 again illustrates that our vision and reality don’t always align. At every point where the white lines intersect our eyes perceive a gray, shadowy blob. If you look directly at one of the intersections though, the blob disappears.

What does this paradox mean for our own calls, and the ways in which we see (or don’t see) what God is up to, observe each other, or even envision ourselves? What does this mean for us in a technological culture consumed with images, being liked and followed by the masses on social media, being “right” in our deepening political polarizations?

Questions for the practice of Examen & Contemplation

- What shimmers for you in this passage?

- How, when and where have you experienced this mysterious paradox of God’s calling – that God often chooses what we wouldn’t, seeing more than we can or do?

- Talk with God about how your limited vision might be keeping you from knowing all of the fullness, goodness and peace God wants for you to know.

Download the PDF study guide for these texts HERE. We’ll use it for our Vocabulary of Faith class @CAPCOakland on Sunday morning.